Should Climbers Be Worried about Scapular Winging? (Scapular Dyskinesis)

Hooper’s Beta Ep. 102

INTRODUCTION

“Scapular winging” is somewhat of a hot topic in the climbing community, and considering how hyper-focused we are on our back and shoulder muscles, it’s easy to see why our scapulas have become so heavily scrutinized.

Strong, mobile shoulders are absolutely essential for climbers and the scapulas are a key part of that system, so it can be quite concerning when we think there’s an issue.

On top of that, this subject can get really confusing, because most of the time when people say “scapular winging” what they actually mean is “scapular dyskinesis.” Informally, the terms are used interchangeably, but in a medical sense that’s not the case and we should know how to differentiate them.

So in this video I want to demystify what these terms actually mean and how serious they are. I’ll also provide you the tools and insight to examine your own shoulders so you can see if this is something you should be concerned about.

SCAPULAR WINGING VS SCAPULAR DYSKINESIS

In the formal sense, “scapular winging” refers to a rare, often debilitating disorder. It’s caused by a failure of the stabilizing tissues that keep the scapula anchored to the rib cage (thorax), creating a prominent, wing-like protrusion. This leads to significant functional limitations, including the inability to elevate the shoulder beyond about 90 degrees.

Scapular dyskinesia, on the other hand, is a broad term used to describe a plethora of dysfunctional or abnormal movement of the shoulder blade. In fact, “dyskinesis,” the singular form of “dyskinesia,” literally just means “bad movement” (“dys” = bad, “kinesis” = movement). As a result, the severity of a scapular dyskinesis can range quite a bit, from “I don’t even feel it” to “mild pinch” to “holy crap I can’t climb.”

Based on those definitions, notice that scapular winging is something you can see while the shoulder is static or at rest, whereas scapular dyskinesia is defined by abnormal movement.

This is an important distinction, because it means scapular dyskinesia cannot be properly identified by simply observing your shoulder at rest. While static tests may lend some insight, a true diagnosis requires analysis of the scapula during movement, making things a bit more complicated.

Now, just for fun, I want to know: do you think it’s okay for “scapular winging” and “scapular dyskinesis” to be used interchangeably by climbers, or do you think we should keep them separate? Let me know down in the comments!

SO WHAT IS “NORMAL” SCAPULAR MOVEMENT?

There are a lot of moving parts needed for shoulder movement, including the humerus, clavicle, scapula, serratus anterior, trapezius muscles, and rhomboids, and if all these structures are working in tandem, the scapula and arm will follow a “normal” pattern of movement.

This is sometimes referred to as “scapulohumeral rhythm” (“SHR”).

While there is some debate over the exact numbers, normal 180-degree overhead motion of the arm involves about 120 degrees of humeral movement with about 60 degrees of scapular rotation.

This rhythm is quite helpful for healthy movement of the shoulder. It helps maintain better positioning of that shallow ball and socket joint, and it improves strength and efficiency in the surrounding muscles.

WHAT IS ABNORMAL SCAPULAR MOVEMENT (DYSKINESIS)?

If any of those structures in the shoulder or back malfunction, the scapulohumeral rhythm can be disrupted, like how Jason’s trip to Bishop disrupted the rhythm of this video… …or how one bad chord can ruin a song.

Muscle weakness, tears, imbalances, nerve damage, weakness in the core, and joint issues can become that bad chord. As a result, the song changes, either as a direct consequence of the malfunction or as an indirect consequence of the “musician” trying to compensate for it.

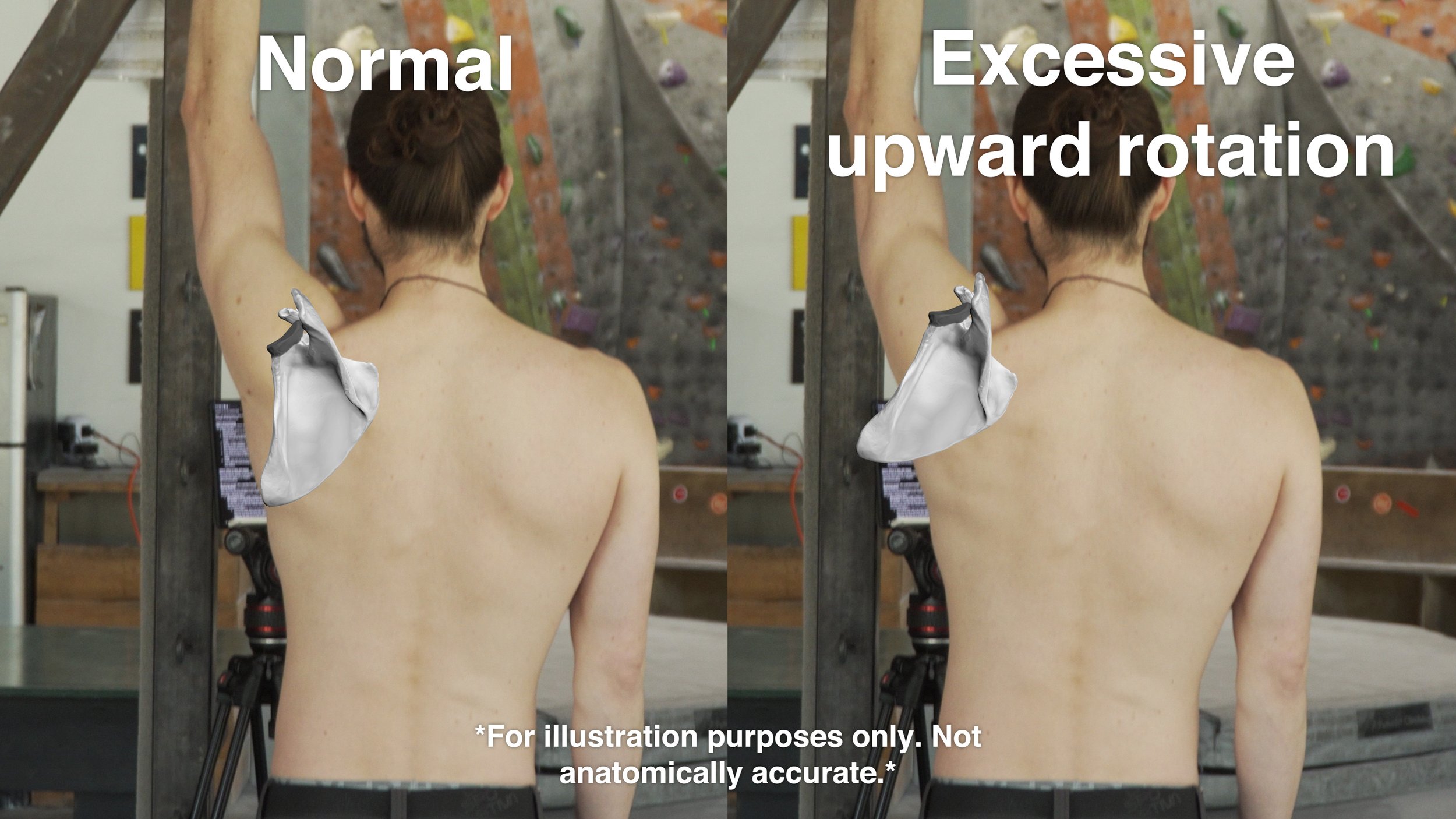

This change in rhythm can manifest in a number of ways. One example was shown in a 2020 study by Kozono et al, where they monitored shoulder movement in patients with rotator cuff tears. Among other things, they found the upward rotation of the scapula in these patients was significantly higher than in uninjured shoulders, particularly in the middle range of motion.

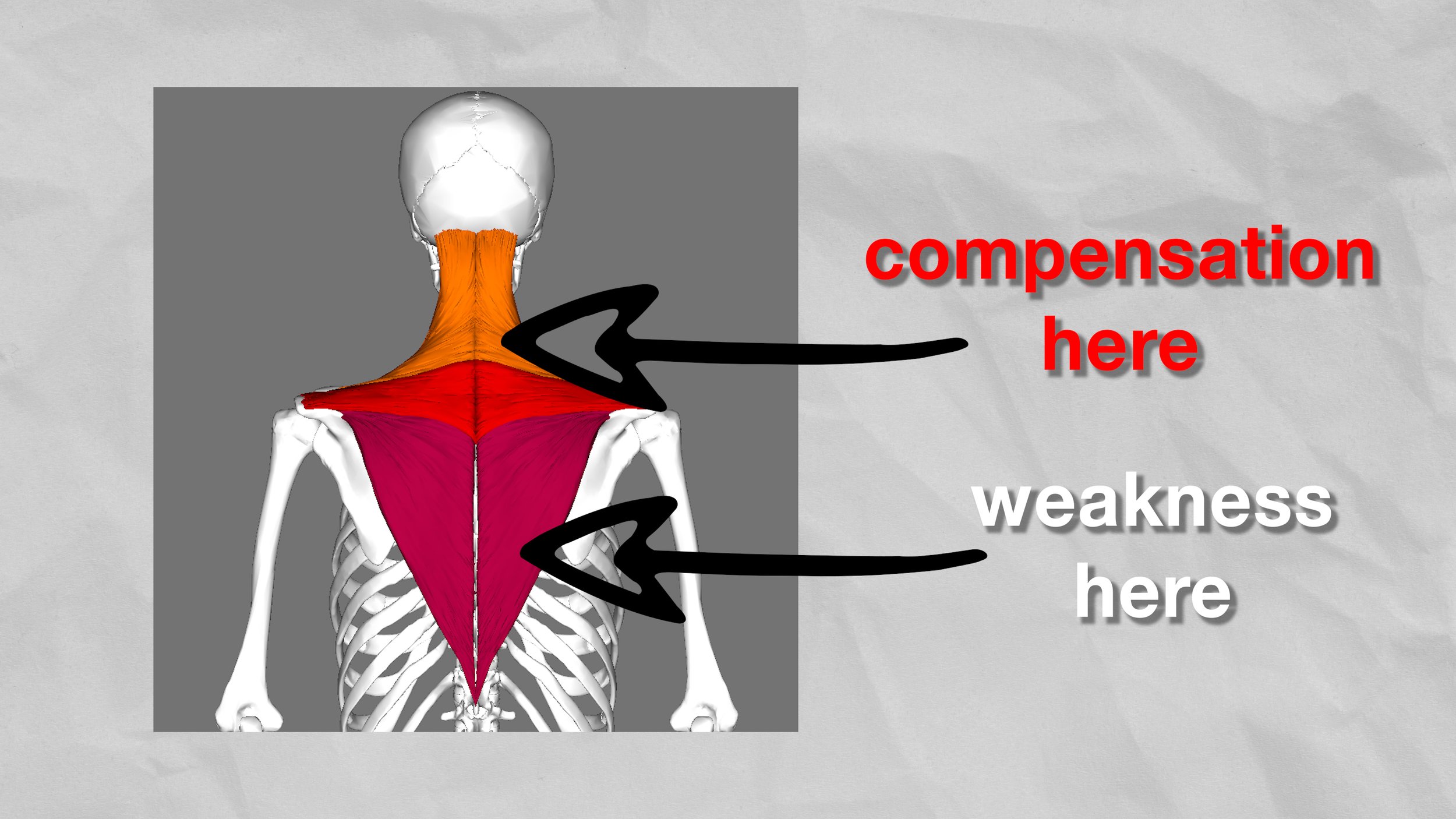

Another example is compensation caused by weakness in the lower trapezius, which may cause issues in the upper trapezius while climbing or training overhead. This can result in a stiff neck and shoulder pain.

DIAGNOSING SCAPULAR DYSKINESIS CAUSES

To get a truly accurate evaluation I recommend seeing a professional because identifying scapular dyskinesis and its causes is not the easiest task.

BUT, I do still think there’s value in educating and examining yourself, so let’s give it a try.

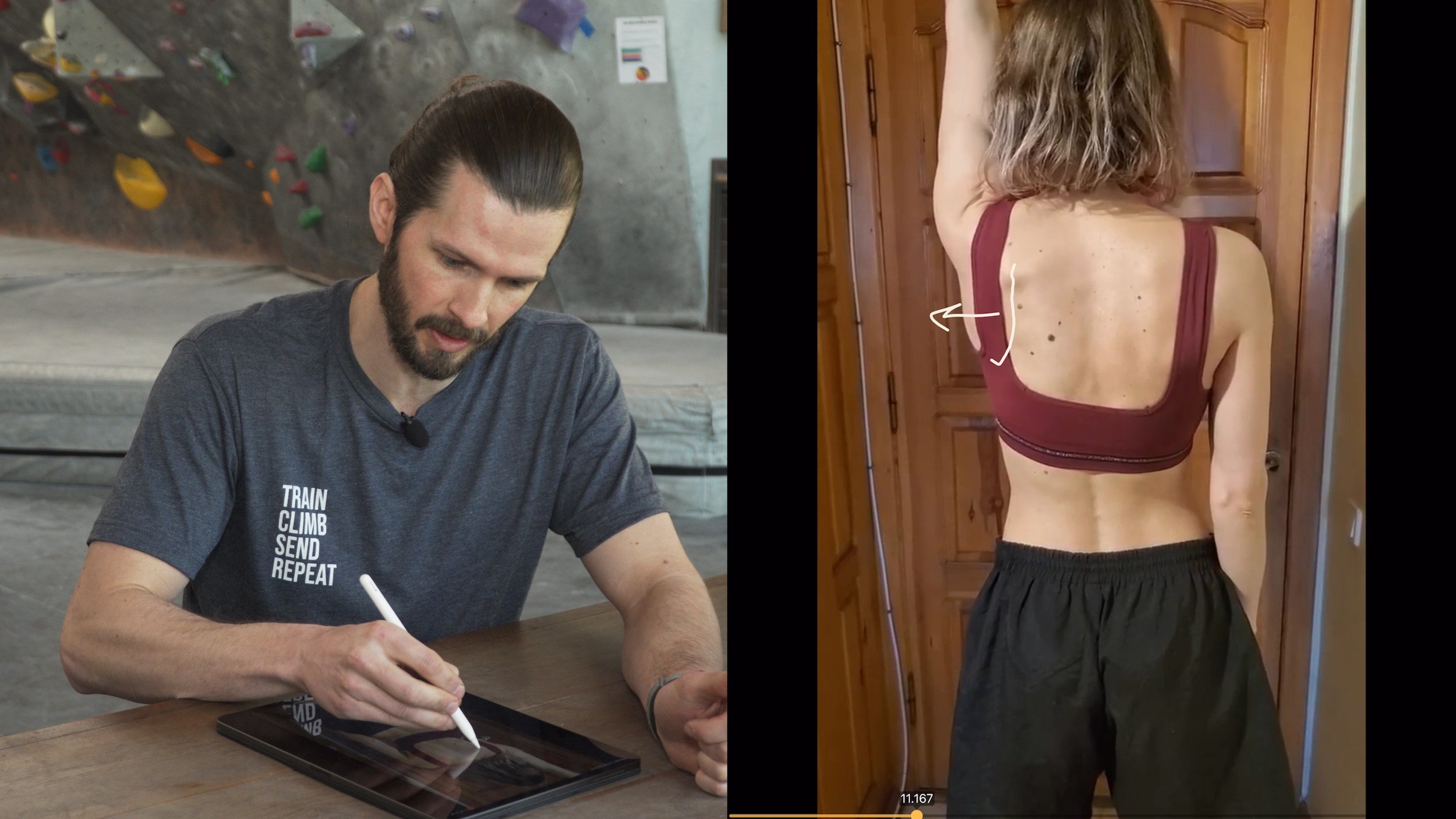

We’ll use simple shoulder flexion and a camera to observe our scapula in motion.

Start with your hands by your side and thumbs pointing forward.

Slowly move one arm forward and up until you have moved through the entire range of motion available to you.

Perform multiple repetitions of this to get a good bearing on your movement.

Now repeat the process on the other arm so you have something to compare to.

If you think you have a subtle issue you can try to make it more obvious by doing all this with a small weight.

Finally, with both arms by your side, retract both your scapula as if you’re trying to have the world’s best posture.

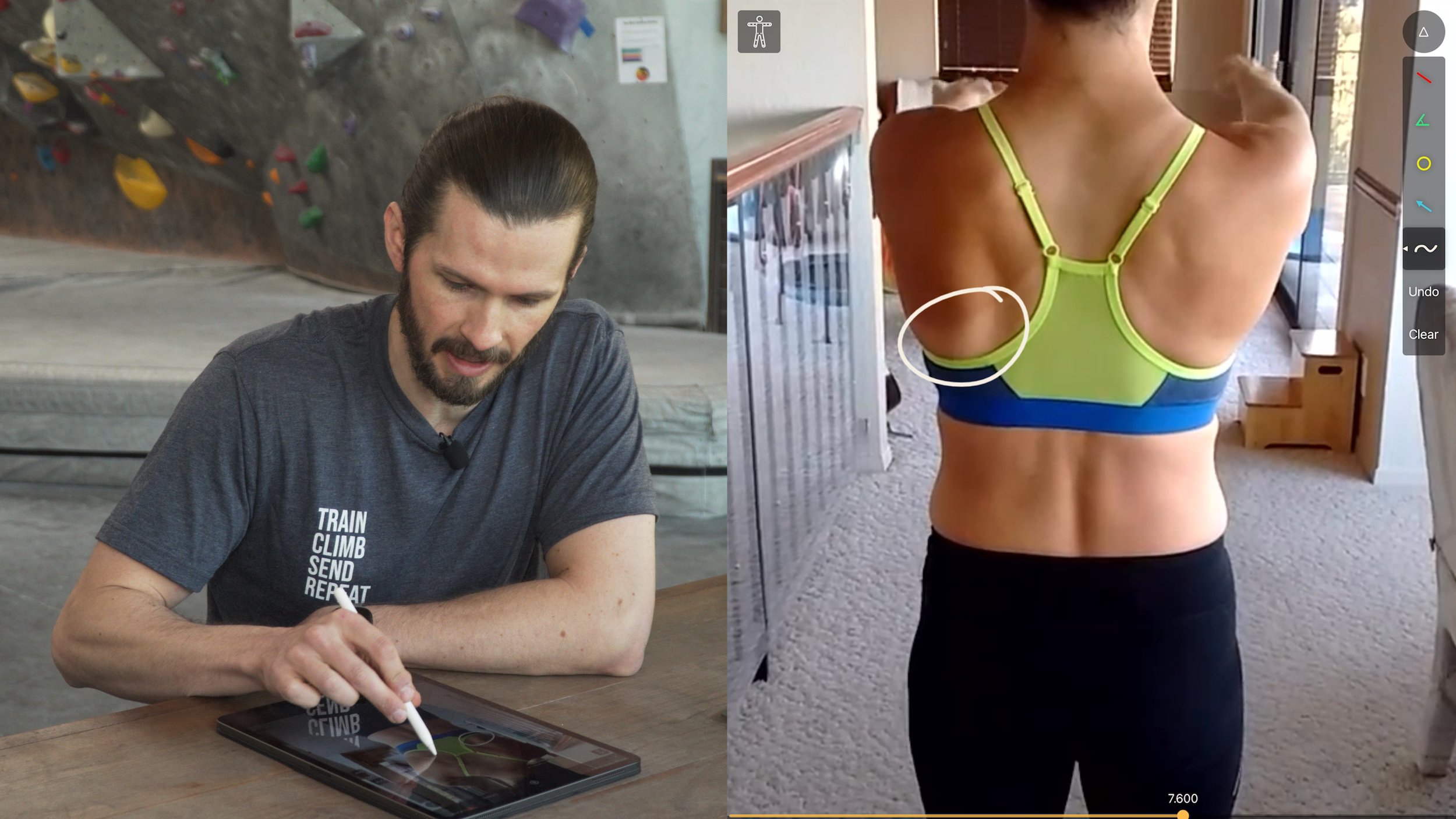

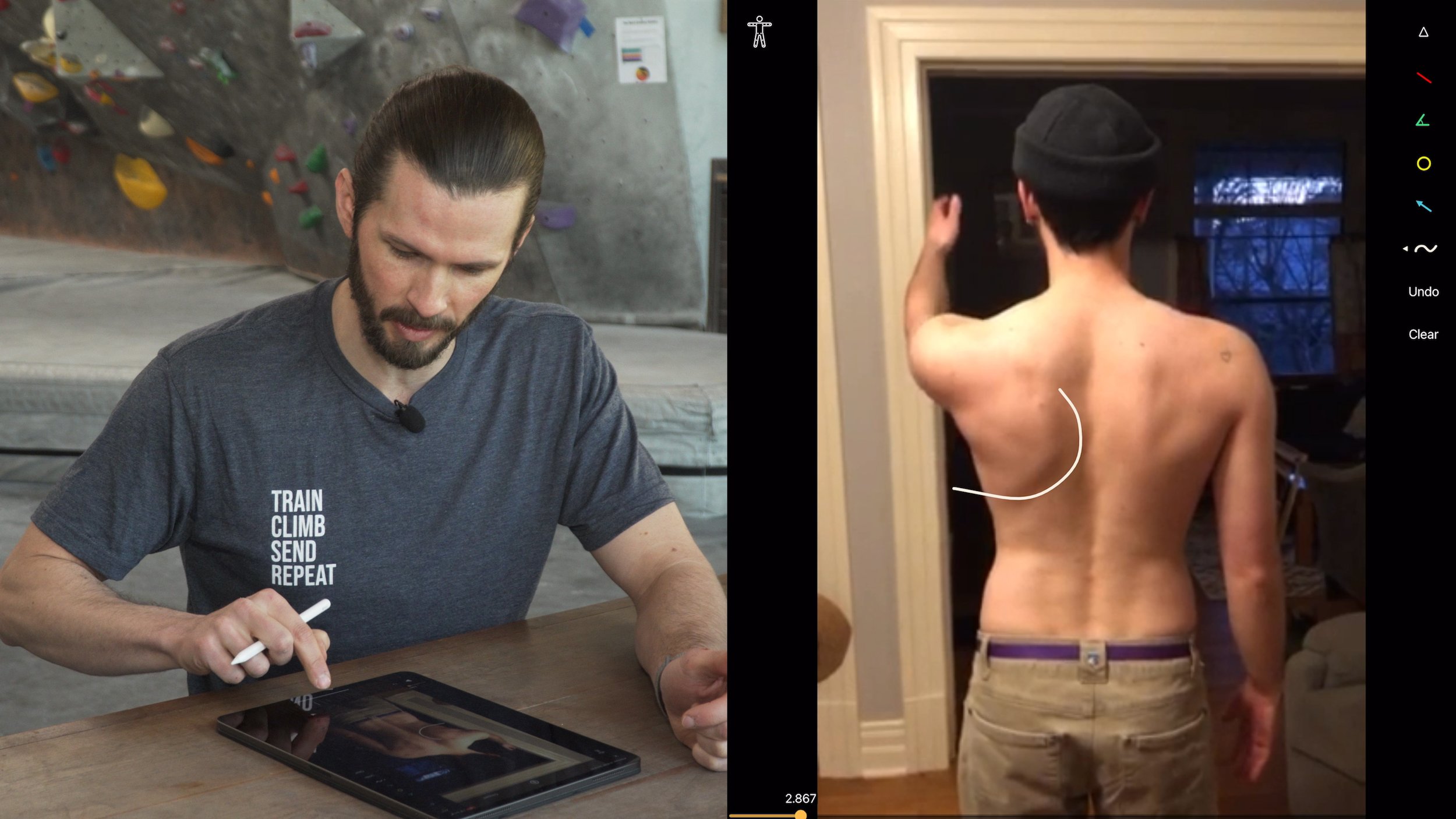

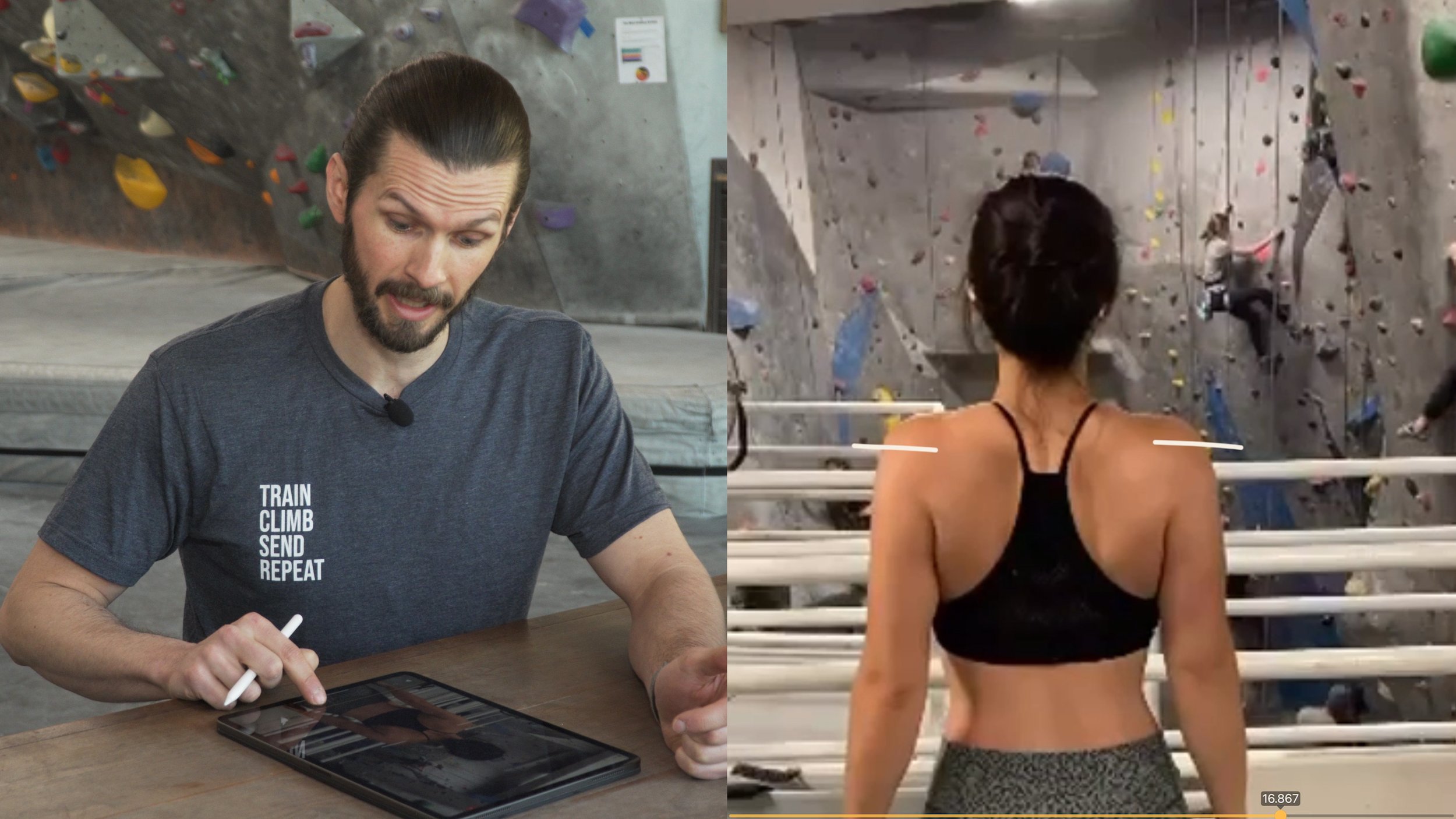

Now to review our footage! I’m gonna use some examples our lovely viewers sent us. If you want to participate in videos like this, follow us on instagram @hoopersbetaofficial!

Here are some common indicators to look for (and keep in mind, even if some of these apply to you, it doesn’t mean you will get a shoulder injury.)

Asymmetrical inferior angle (“bottom point”) of the scapula: If the inferior angle is more prominent on one side or is significantly protruding upon elevation of the arm, this may indicate weakness in your serratus anterior.

Increased upward rotation of the scapula: As noted by the aforementioned research paper, if there is significantly more upward rotation in one scapula compared to the other, it may be a result of a rotator cuff tear.

Decreased upward rotation of the scapula: If the scapula is not upwardly rotating, this may be due to weakness or decreased kinesthetic awareness of the lower trapezius. If this is associated with a pinching discomfort at ~80-120 degrees of elevation, this is a sign of shoulder impingement.

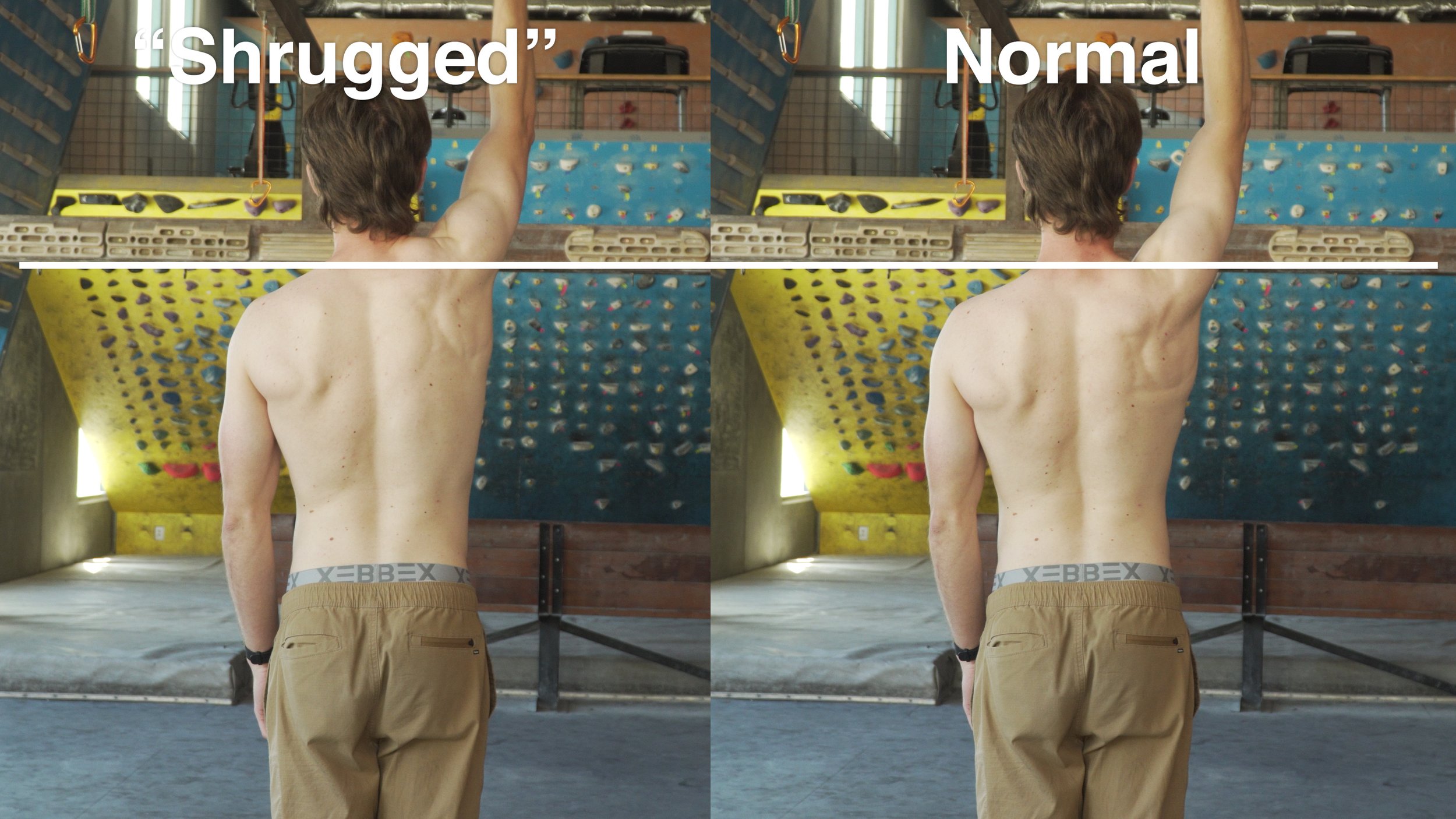

Shifting upward / shrugging of the scapula: If the shoulder shrugs up during the movement, it may be due to weakness of the lower trap, decreased kinesthetic awareness of the lower trap, or overcompensation in the upper trap.

Excessive scapular protraction during elevation: If there is significant protraction of the scapula, there may be weakness in the rhomboids, middle trap, or lower trapezius.

Inability to properly retract the scapula: If you can’t retract your scapula without compensation or shrugging in the upper trap, it may indicate weakness or lack of kinesthetic awareness of the lower trap.

There are also a few indicators to look for while your shoulder is at rest that may or may not correspond to scapular dyskinesis:

Indent on the scapula: May indicate external rotator weakness.

Medial (“inside”) border significantly elevated/protruding: May indicate serratus anterior weakness or the more severe scapular winging.

Inferior angle more prominent: May indicate lower fiber of serratus anterior weakness or rhomboid weakness.

Protracted scapula: May be due to weakness in the middle back (rhomboids, mid trap, low trap) and/or potential tightness in the pec minor / major.

Finally, here’s a test you can do…. If you have friends that is!

The scapula assist test (from their article): “the examiner applies gentle pressure to assist scapular upward rotation and posterior tilt as the patient elevates the arm (Fig. 4). A positive result occurs when the painful arc of impingement symptoms is relieved and the arc of motion is increased.”

Now, before you get all worried that there might be something wrong with you, hold on!

WHY YOU SHOULDN’T OBSESS ABOUT THIS

I highly recommend you do not obsess over the minutiae of every joint angle, muscle activation pattern, and asymmetry in your body, even if you do show some signs of dyskinesis. Why?

Emile: Because it’s not a big deal, bro.

Jason: Well, kind of. While scapular dyskinesis is definitely something you want to address if it’s causing you pain and inhibiting the function of your shoulder, mild dyskinesis is not something to worry about too much.

For one thing, our bodies are so adaptable and varied that hyper-analyzing won’t necessarily help you -- possibly even the opposite.

For example, you could have a three-degree variation in your shoulder that’s been there your whole life, but after an six-day climbing trip you start getting a bit of pain in your shoulder and only now do you notice that small variation and as a result you’re freaking out thinking that you might have some horrible shoulder dysfunction.

Sure, there might be a small issue with your shoulder that you can work on OR you just overworked your shoulders and your body is telling you to chill. Either way, it’s not a death sentence, so don’t let it ruin your psych.

Two, as you now know, movement of the shoulder is quite complicated, and while I’m all for educating yourself on training and rehab, the reality is most people don’t have the expertise or equipment to thoroughly assess themselves in this situation.

Remember that Kozono study I mentioned earlier? They used radiographs and CT scans to produce 3D models of their subjects which they then studied to obtain their results. Not exactly a simple evaluation! Of course, that level of analysis won’t be needed for most patients, but a true diagnosis will likely still require an expert with lots of experience in shoulder mechanics.

OKAY, NOW WHAT?

If you’ve followed my advice thus far, you should have a decent idea of what might be causing your scapula issues AND you should not be freaking out about it. Now you simply need to strengthen the muscles associated with the issues you identified in the diagnosis section.

Here’s a nifty chart to help figure that out.

If you have weak shoulders in general, I recommend allocating a good part of your training to correcting that. If you think you have a more isolated weakness, then you can start by focusing on that issue specifically.

We actually have a whole playlist of videos for climbing-related shoulder strengthening if that’s your jam. For maximal results and a more personalized experience, though, I recommend contacting a PT like me or a knowledgeable coach like our friend Dan Beall (#shamelessplug).

And finally, if you’d like us to make a separate video specifically about how to fix scapular dyskinesis, give this video a thumbs up and leave us a comment down below!

Until next time

Train your scapula so you don’t even need to climb because you have awesome wings that let you send by simply flying to the top. Aaaand repeat, but now with a Red Bull sponsorship.

RESEARCH

Title

Current concepts: scapular dyskinesis

Citation

Kibler WB, Sciascia A. Current concepts: scapular dyskinesis. Br J Sports Med. 2010 Apr;44(5):300-5. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058834. Epub 2009 Dec 8. PMID: 19996329.

Key Takeaways

Background

Scapular movement is a composite of three motions—upward/downward rotation around a horizontal axis perpendicular to the plane of the scapula, internal/external rotation around a vertical axis through the plane of the scapula and anterior/posterior tilt around a horizontal axis in the plane of the scapula

The clavicle acts as a strut for the shoulder complex, connecting the scapula to the central portion of the body. This allows two translations to occur—upward/downward translation on the thoracic wall and retraction/protraction around the rounded thorax

When the humerus moves into elevation, clavicular elevation, retraction and posterior axial rotation occurs at the sternoclavicular joint, while scapular internal rotation, upward rotation and posterior tilting occur at the acromioclavicular join

Because of the important but minimal bony stabilisation of the scapula by the clavicle, dynamic muscle function is the major method by which the scapula is stabilised and purposefully moved to accomplish its roles.

Muscle activation is coordinated in taskspecifc force couple patterns to allow stabilisation of position and control of dynamic coupled motion.

Abnormal scapular motion and/or position have been collectively called ‘scapular winging’, ‘scapular dyskinesia’ and more appropriately ‘scapular dyskinesis’.

Scapular winging refers to prominence of the medial border of the scapula, which is most often associated with long thoracic nerve palsy, and in some cases, overt scapular muscle weakness.

Scapular dyskinesia by strict defi nition implies that a loss of voluntary motion has occurred. However, only the scapular translations (elevation/depression and retraction/protraction) can be performed voluntarily, whereas the scapular rotations are accessory in nature

Scapular dyskinesis (‘dys’—alteration of, ‘kinesis’— movement) is a collective term that refers to movement of the scapula that is dysfunctional. Scapular dyskinesis has been identified by a group of experts as: (1) abnormal static scapular position and/or dynamic scapular motion characterised by medial border prominence; or (2) inferior angle prominence and/or early scapular elevation or shrugging on arm elevation; and/or (3) rapid downward rotation during arm lowering

However, static position and dynamic motion are two separate entities, so when describing the static appearance of the scapula and if an asymmetry is observed, it should be referred to as ‘altered scapular resting position’ rather than ‘scapular dyskinesis’.

Scapular dyskinesis is a non-specific response to a painful condition in the shoulder rather than a specific response to certain glenohumeral pathology. Scapular dyskinesis has multiple causative factors, both proximally (muscle weakness/imbalance, nerve injury) and distally (acromioclavicular joint injury, superior labral tears, rotator cuff injury) based. This dyskinesis can alter the roles of the scapula in the scapula–humeral rhythm. It can be due to alterations in the bony stabilizers, alterations in muscle activation patterns, or strength in the dynamic muscle stabilizers.

Dynamic Scapular Stability

The lower trapezius has often been identified as an upward rotator of the scapula because it maintains its long moment arm during the full range of upward rotation. However, it also plays a role as a scapular stabiliser when the arm is lowered from an elevated position. During the descent or return from upward elevation, the well-positioned lower trapezius, when operating efficiently, helps maintain the scapula against the thorax

The serratus anterior helps produce scapular upward rotation, posterior tilt and external rotation while stabilizing the medial border and inferior angle, which prevents scapular winging

The scapular position that allows optimal muscle activation of the shoulder joint muscles to occur is that of retraction and external rotation

Scapular retraction is an obligatory and integral part of a normal scapula–humeral rhythm in coupled shoulder motions and functions.

SCAPULAR DYSKINESIS AND SHOULDER INJURY

AC joint separations

There is an uncoupling of the scapulohumeral complex such that the scapular stabilizing muscles are not able to maintain appropriate positioning of the glenohumeral and acromiohumeral joints. There is a subsequent loss of rotator cuff strength and function that can only be restored by retraction of the scapula and restoring the pivot point of the acromioclavicular joint. Surgical correction of the damaged anatomy in high-grade acromioclavicular separations should be based on restoring the coupled clavicular/scapular motion.

Impingement

Increased upper trapezius activity, imbalance of upper trapezius/lower trapezius activation and decreased serratus anterior activity have been reported in patients with impingement.

Title

Citation

Hickey D, Solvig V, Cavalheri V, Harrold M, Mckenna L. Scapular dyskinesis increases the risk of future shoulder pain by 43% in asymptomatic athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Jan;52(2):102-110. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097559. Epub 2017 Jul 22. PMID: 28735288.

Title

Scapular Dyskinesis: From Basic Science to Ultimate Treatment

Citation

Longo UG, Risi Ambrogioni L, Berton A, Candela V, Massaroni C, Carnevale A, Stelitano G, Schena E, Nazarian A, DeAngelis J, Denaro V. Scapular Dyskinesis: From Basic Science to Ultimate Treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Apr 24;17(8):2974. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082974. Erratum in: Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 May 27;17(11): PMID: 32344746; PMCID: PMC7215460.

Title

Citation

Hogan C, Corbett JA, Ashton S, Perraton L, Frame R, Dakic J. Scapular Dyskinesis Is Not an Isolated Risk Factor for Shoulder Injury in Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2021 Aug;49(10):2843-2853. doi: 10.1177/0363546520968508. Epub 2020 Nov 19. PMID: 33211975.

Title

Prevalence of Scapular Dyskinesis in Overhead and Nonoverhead Athletes: A Systematic Review

Citation

Burn MB, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM, Liberman SR, Harris JD. Prevalence of Scapular Dyskinesis in Overhead and Nonoverhead Athletes: A Systematic Review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016 Feb 17;4(2):2325967115627608. doi: 10.1177/2325967115627608. PMID: 26962539; PMCID: PMC4765819.

Title

Citation

Nodehi Moghadam A, Rahnama L, Noorizadeh Dehkordi S, Abdollahi S. Exercise therapy may affect scapular position and motion in individuals with scapular dyskinesis: a systematic review of clinical trials. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020 Jan;29(1):e29-e36. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.05.037. Epub 2019 Aug 13. PMID: 31420226.

Title

Citation

Kozono N, Takeuchi N, Okada T, Hamai S, Higaki H, Shimoto T, Ikebe S, Gondo H, Senju T, Nakashima Y. Dynamic scapulohumeral rhythm: Comparison between healthy shoulders and those with large or massive rotator cuff tear. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2020 Sep-Dec;28(3):2309499020981779. doi: 10.1177/2309499020981779. PMID: 33355033.

Key Takeaways

First, external rotation of the scapula was significantly greater in the RCT group than in the control group in the late phase of the full external rotation movement with arm at the side

With regard to external rotation of the scapula, significant between group differences were identified at two positions of humeral external rotation, 30 and 45

Second, there were significant differences in SHR, scapular posterior tilting and scapular upward rotation between the RCT and control group during scapular plane abduction

Significant differences in the SHR were identified between the RCT and control groups during scapular plane abduction, with the SHR being significantly smaller in the RCT group than in the control group at every point between 60 and 105 of humeral abduction.

Additionally, scapular upward rotation was significantly greater in the RCT group than in the control group at every point between 105 and 130 of humeral abduction.

Moreover, we also identified that the posterior tilt position of the scapula was 7 greater, overall, in the RCT group than in the control group during scapular plane abduction.

This increase in posterior tilting of the scapula in the presence of a RCT would reduce the subacromial space and could contribute to the painful arc.

In the presence of a RCT, we identified greater scapulothoracic motion in the late phase of external rotation with arm at the side and greater scapulothoracic motion and less glenohumeral motion in the mid-phase of scapular plane abduction

Title

Citation

Scibek, J. S., & Carcia, C. R. (2012). Assessment of scapulohumeral rhythm for scapular plane shoulder elevation using a modified digital inclinometer. World journal of orthopedics, 3(6), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v3.i6.87

Key Takeaways

The scapula contributed 2.53% of total motion for the first 30 degrees of shoulder elevation, between 20.87% and 37.53% for 30o-90o of shoulder elevation, and 52.73% for 90o-120o of shoulder elevation.

Disclaimer:

As always, exercises are to be performed assuming your own risk and should not be done if you feel you are at risk for injury. See a medical professional if you have concerns before starting new exercises.

Written and Presented by Jason Hooper, PT, DPT, OCS, SCS, CAFS

IG: @hoopersbetaofficial

Filming and Editing by Emile Modesitt

www.emilemodesitt.com

IG: @emile166