Could Cueing Revolutionize Your Climbing Progression?

Hooper’s Beta Ep. 133

Intro

What if I told you that if you perform an exercise at a fast pace, you could get 10% more strength gains than if you perform it at an average pace? Now, what if I told you it’s okay if you can’t actually move much faster, as long as you’re simply trying to? You’d start doing it immediately, right? Well, those are real results from a 2012 study, and it’s part of a growing body of evidence demonstrating the power of intention in physical performance. [14]

The implications of this concept are so huge, yet so underutilized by your average climber, I believe it could actually revitalize or revolutionize many people’s progression. So in this video we’re going to talk about how climbers can harness the power of intention to benefit strength, speed, coordination, endurance, and skill acquisition. And we’re going to do it by discussing intention’s practical offspring, cueing.

What Is It?

So what is cueing? Well, it can take many forms.

Cueing can be simple, like consciously thinking “crush the hold” on terrible pinches and finding we can hold on better than before.

Cueing can also be complex, like visualizing our exact muscle engagement and spatial orientation on a climb so thoroughly that our body learns the movement without being on the wall.

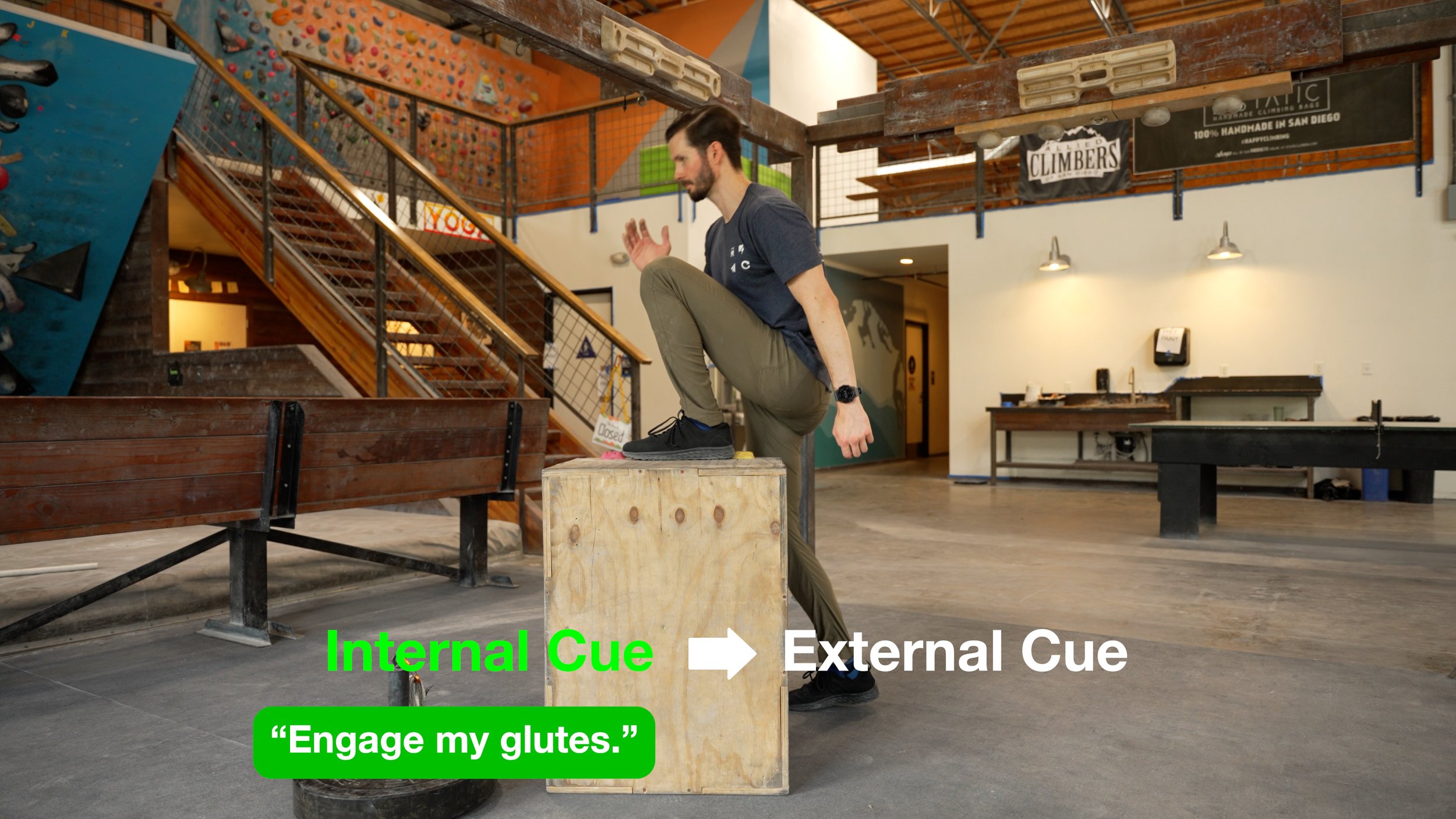

Cueing can direct our attention inward, to specific internal sensations, like focusing on engaging our glutes during a dynamic move and finding we maintain better body tension.

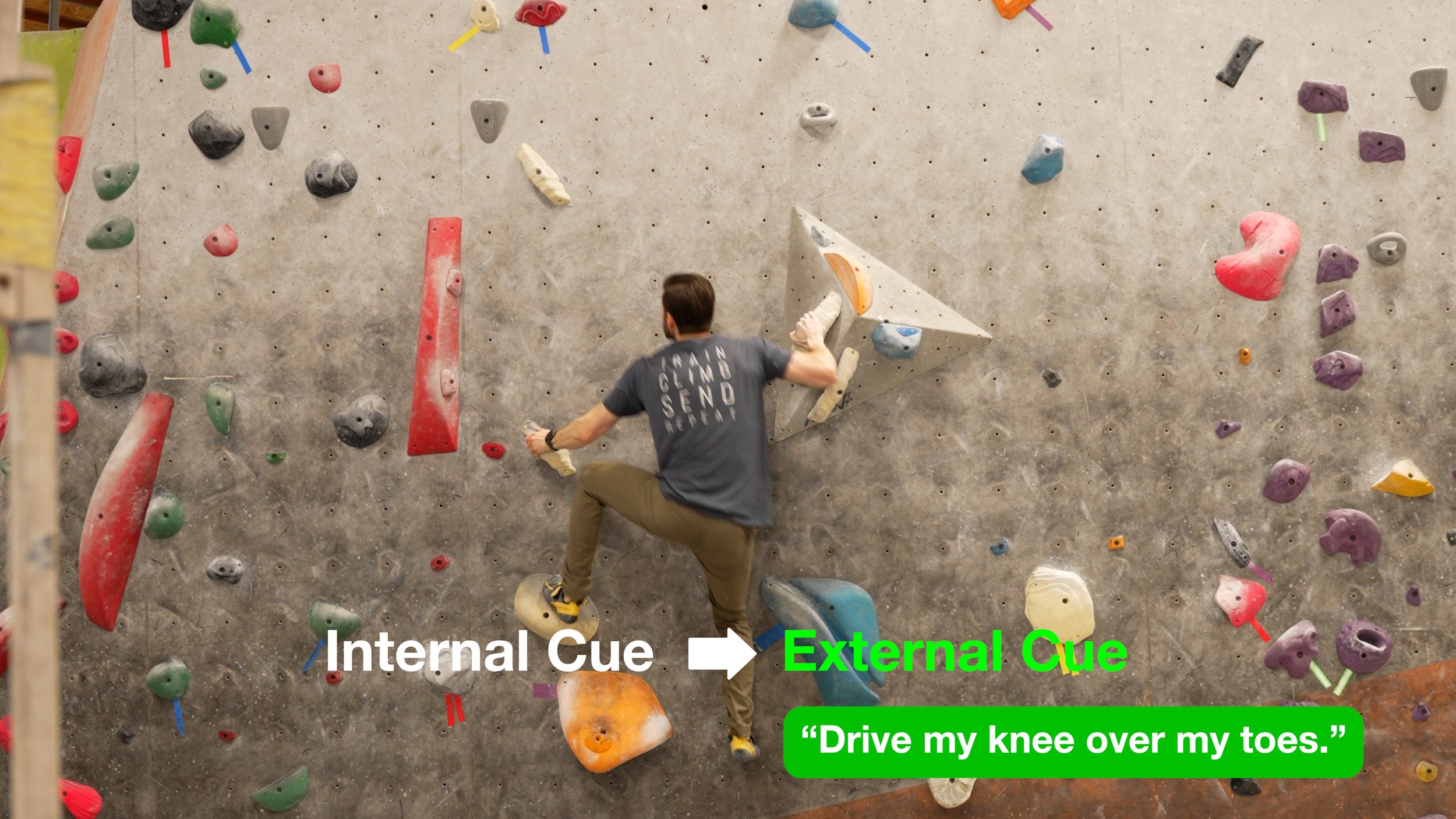

Cueing can also direct our attention outward, to external or environmental targets, like thinking “get my chest to the bar” during a pullup and seeing that our form naturally improves.

As you can see, a cue is just a practical way to apply a specific intention. What I love is that, rather than always trying to remember random tricks we’ve heard, thinking in terms of cues helps us focus on identifying the problem we’re facing, coming up with a specific intention that could solve it, and creating a cue that puts the intention into practice. It also encourages a present, problem-solving mindset rather than the distracted, just-going-through-the-motions attitude we can sometimes find ourselves in.

Sounds pretty good, right? But why am I saying it could be “revolutionary”?

Well, it’s not just because of the numerous studies showing its performance benefits, which we’ll talk about soon. The bigger reason is because cueing, and more broadly, intention, when adopted as a mindset, helps solve what is quite possibly the most ubiquitous impediment to progress climbers face, whether they know it or not. Allow me to explain.

What’s the Big Deal?

Climbing is, after all, both a skill sport and a bodyweight sport -- it relies on learned coordination, tactics, and techniques just as much as physical prowess. And yet, despite wanting to improve, most climbers don’t take a systematic approach to making it happen, especially with the skill side of things. While we like to hope our intuition will magically guide us toward our epic goals as long as we just keep showing up at the gym, that simply doesn’t work for the vast majority, especially if our intuition is based on a shaky foundation of skills to begin with.

In short, most climbers facing chronic plateaus and… this feeling... are experiencing the pitfalls of practicing with a lack of specific intention.

If we look at the science behind how humans learn, including movement learning (like climbing), it’s apparent why lack of intention is such a problem.

In the cognitive stage, we receive instructions (from ourselves or someone else) about how to perform a movement and then we practice it. Because of high variability and errors, a lot of our attention is required to continuously integrate feedback and make adjustments. Once we’ve smoothed things out, we enter the associative stage, in which we can execute the movement with greater accuracy and refinement. But, much focus is still required to learn the move well enough to enter the final stage: autonomous. This is where the movement has become almost automatic, the performance faster and more fluid. Little attentional resources are now needed to execute it, and even the area of the brain that’s most active shifts away from our frontal lobes [10].

As you can see, the first two stages are heavily reliant on specific, intentional practice. If we remove intention from this equation, we hinder our ability to learn.

To put this in more practical terms, imagine a climb with a dynamic lateral move. To make the move, we’ll need to drive our knee over our toes to push us toward the next hold, keeping our hips open while engaging our glutes to stay close to the wall. However, we don’t consciously identify this, we haven’t specifically practiced this type of movement much in the past, and like most climbers we have generally poor glute engagement. So, when we hop on the wall hoping our intuition will take care of things, our knee doesn’t drive far enough over, our quads engage more than our glutes, and we get pushed off the wall. If we don’t try to intentionally identify and fix this problem, we’ll likely gain no new insight or skills while also going on to make the same mistake on future climbs. Or, we can try to fix the issue, using simple cues like “engage my glutes” or “get my knee past my toes” to practice the muscle engagement, gain the coordination, and make the move. With enough practice, we can even enter the third stage of motor learning in which this movement becomes automatic. We’ve then mastered a new climbing skill and bolstered our foundation!

In summary, cueing reintroduces us to active, intentional practice, shifting us away from passivity and stagnation. Cueing can readily facilitate better movement learning while also directly enhancing performance. With consistency, this leads to drastically improved skill acquisition, robust foundations of expertise, and ultimately better climbing performance compared to non-intentional approaches.

What Type of Cue Should We Use?

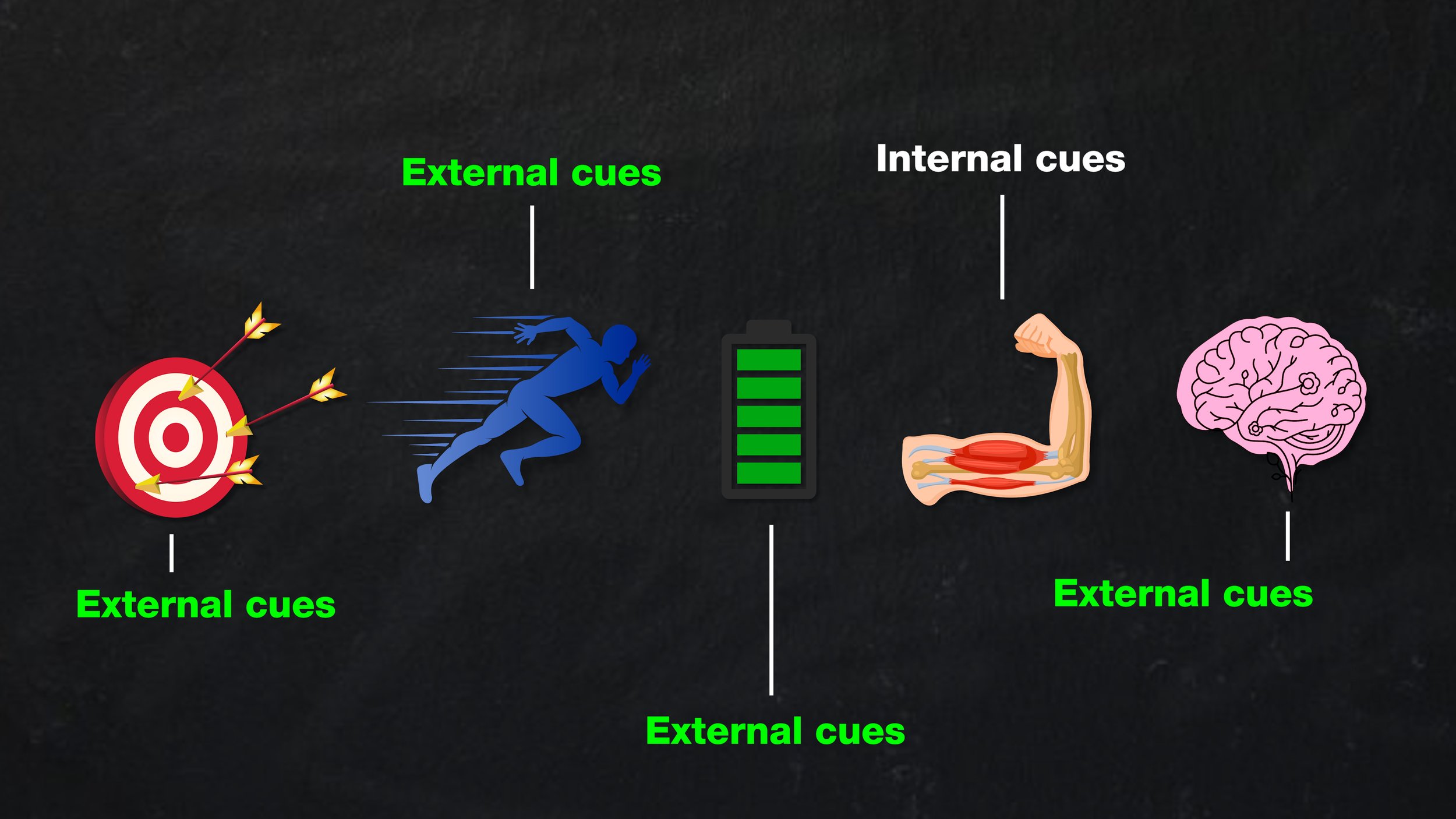

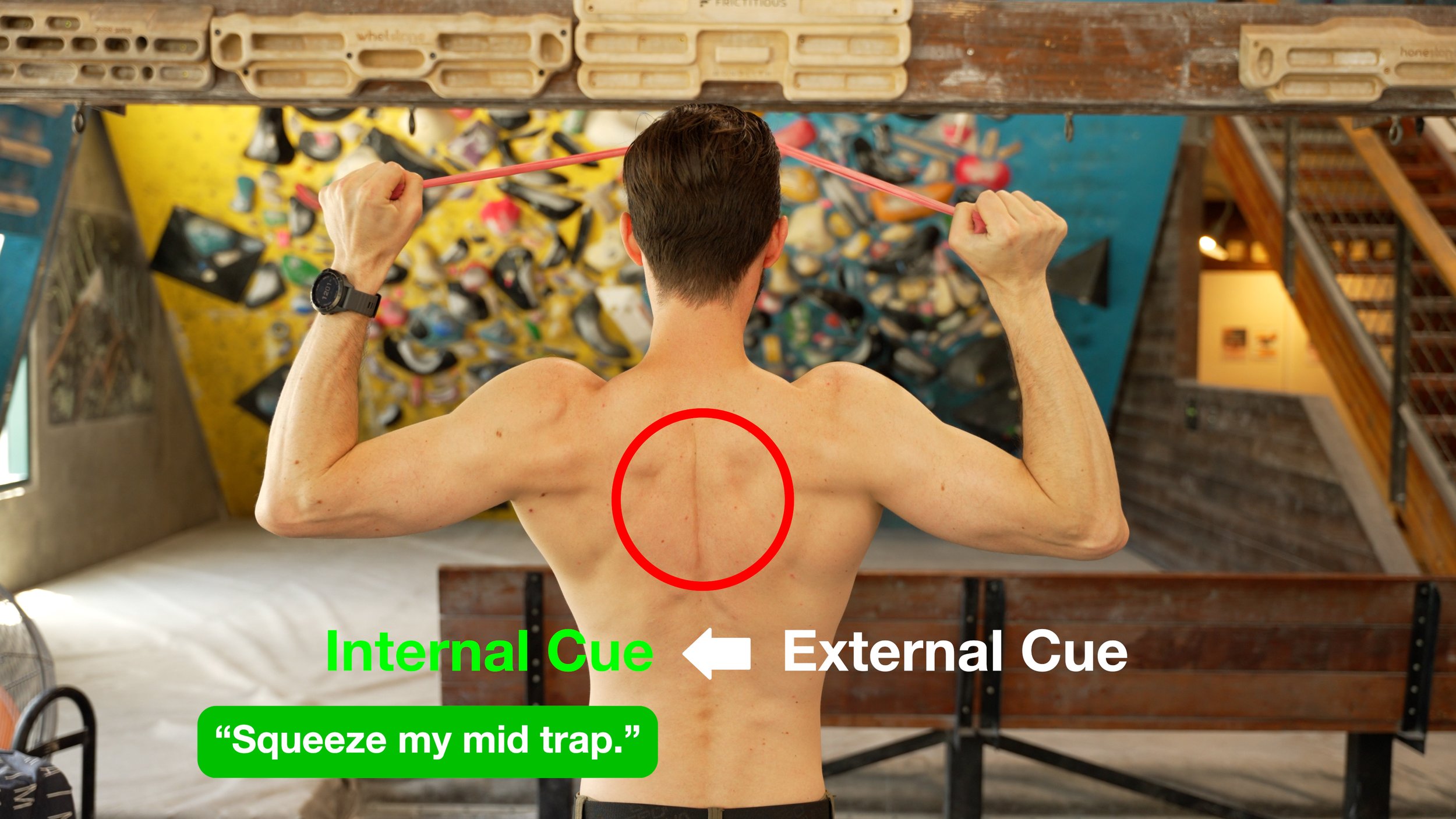

So, what kinds of cues should we actually use? As we implied earlier, there are two types, known as internal cues and external cues, which are useful for different purposes.

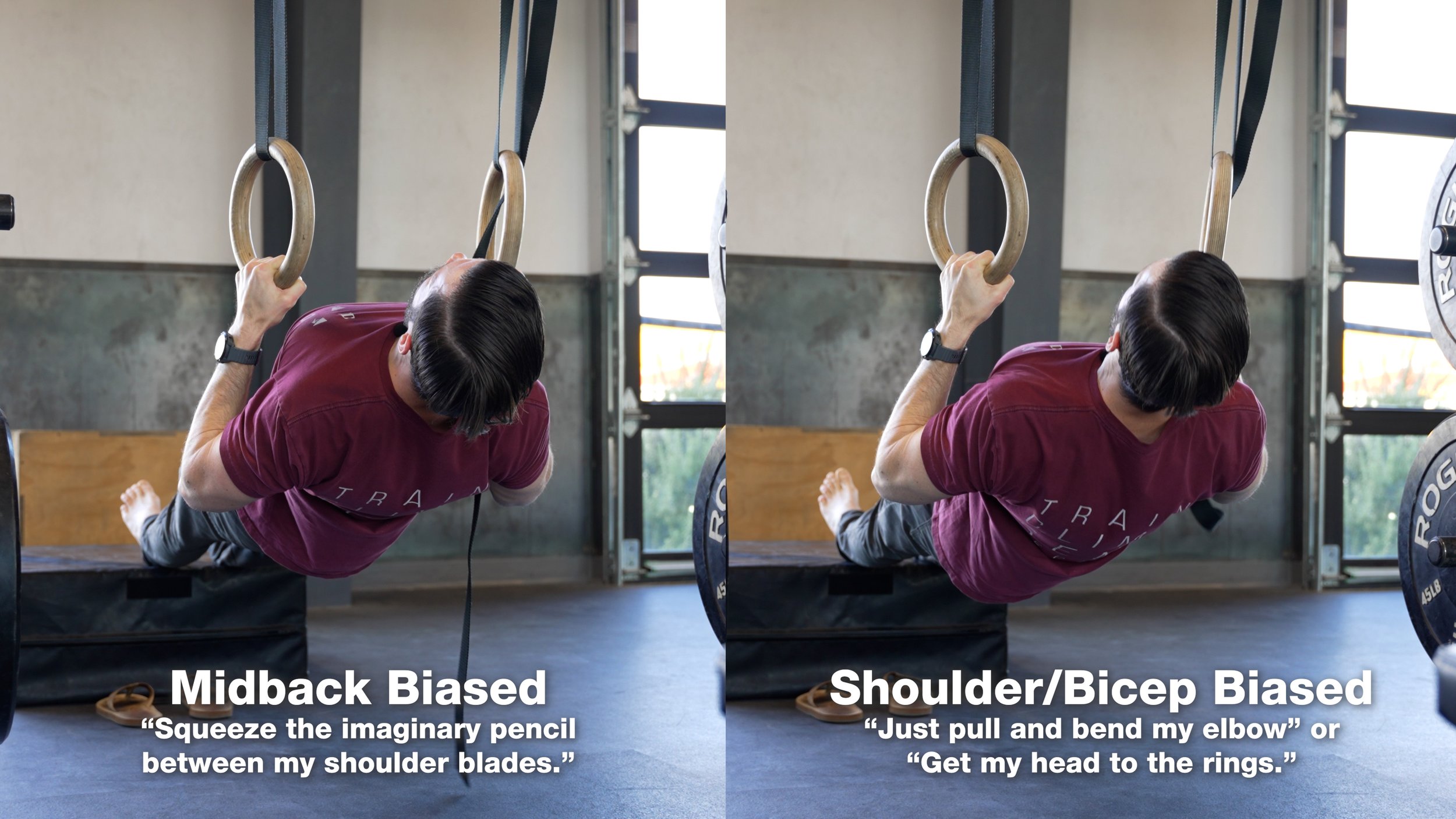

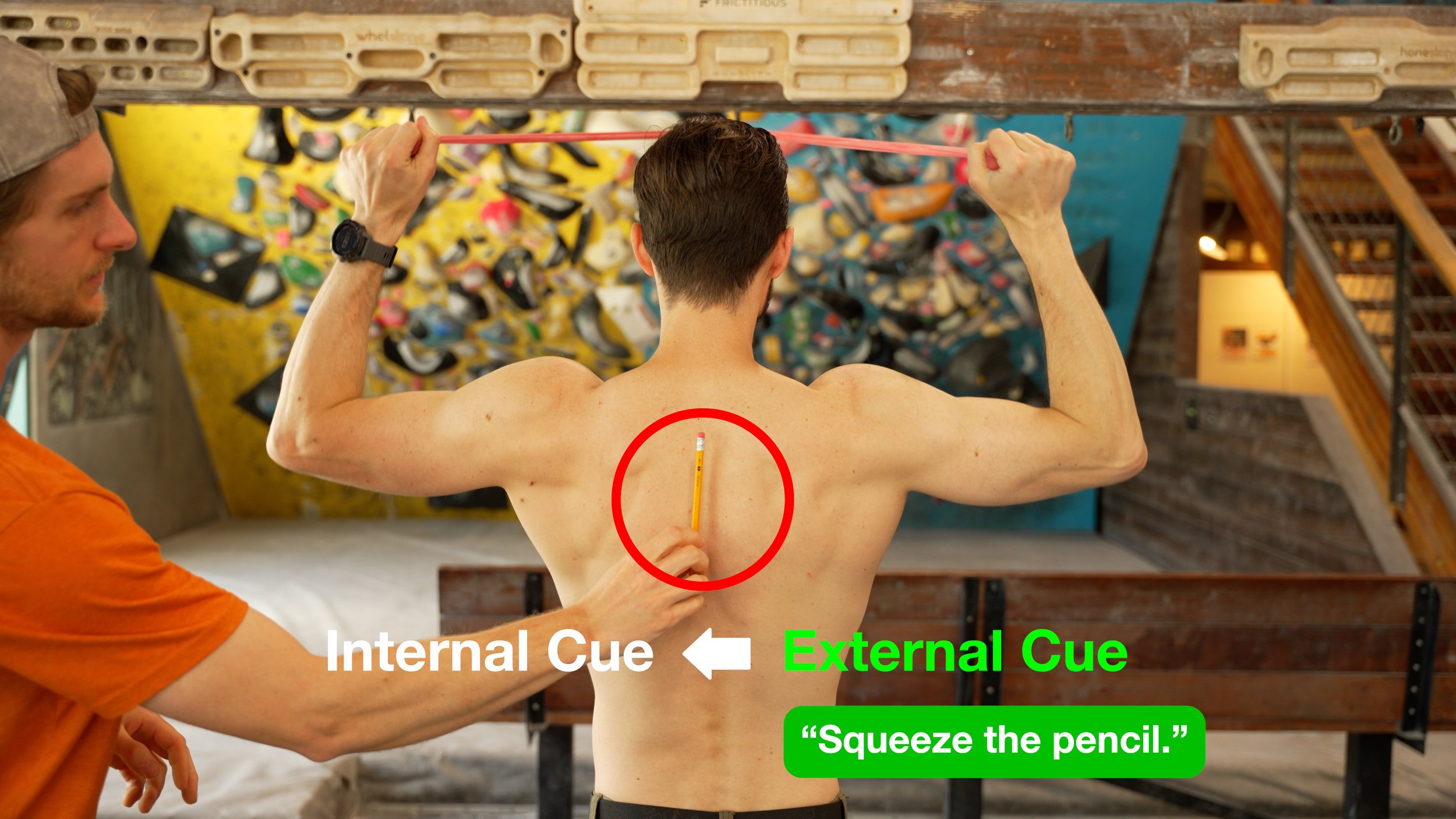

Internal cues create an inward intention. They promote greater bodily awareness by consciously regulating aspects of our body that we typically wouldn’t, allowing us to reduce unwanted activation or movement compensations. Whether it’s improving our face-pull form by focusing on our middle trap, keeping our hips close to the wall by engaging our glutes, or maximizing hypertrophic stimulus by zoning in on our bicep contraction, internal cues are generally best when we need to focus on specific muscle engagement.

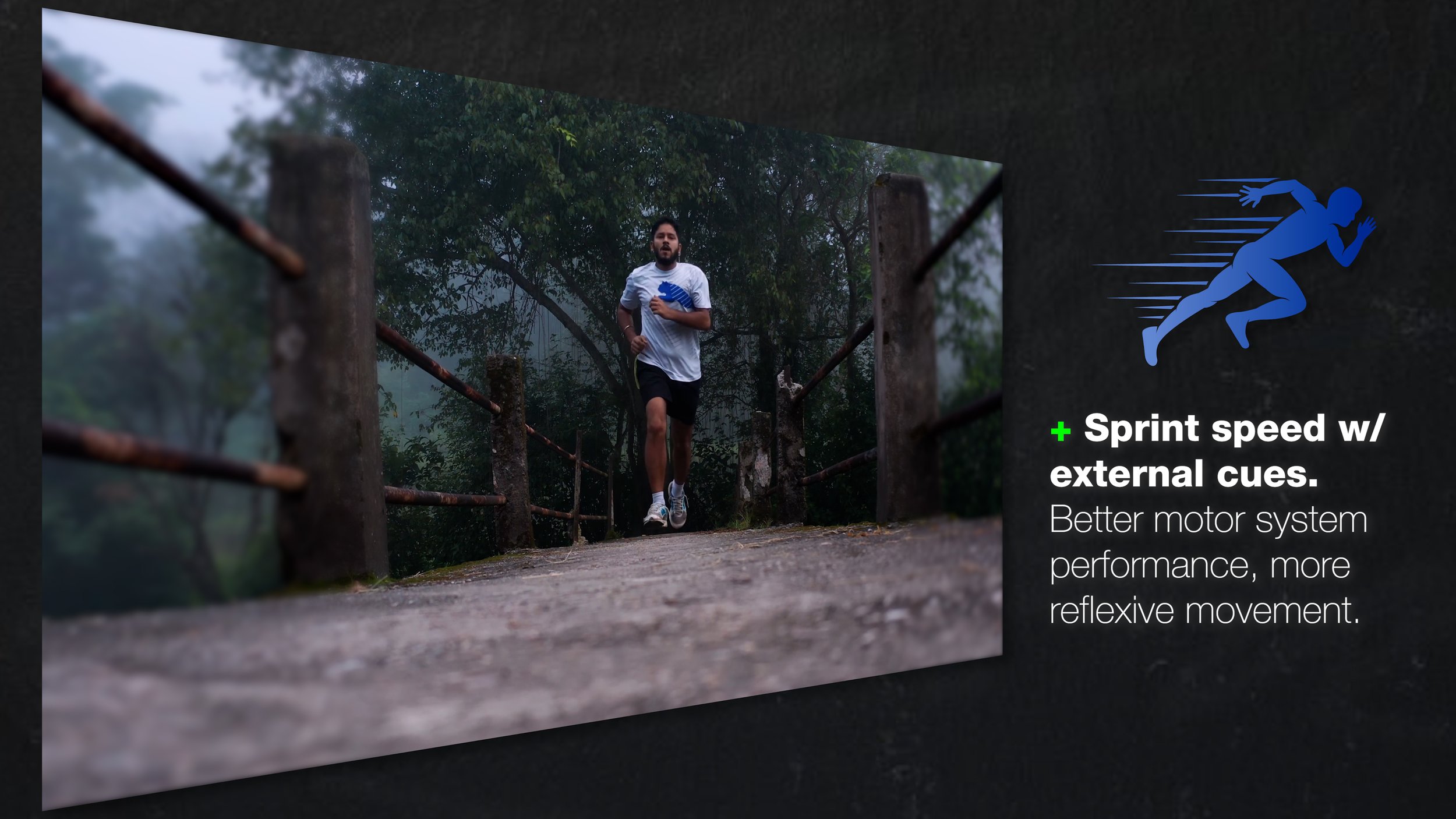

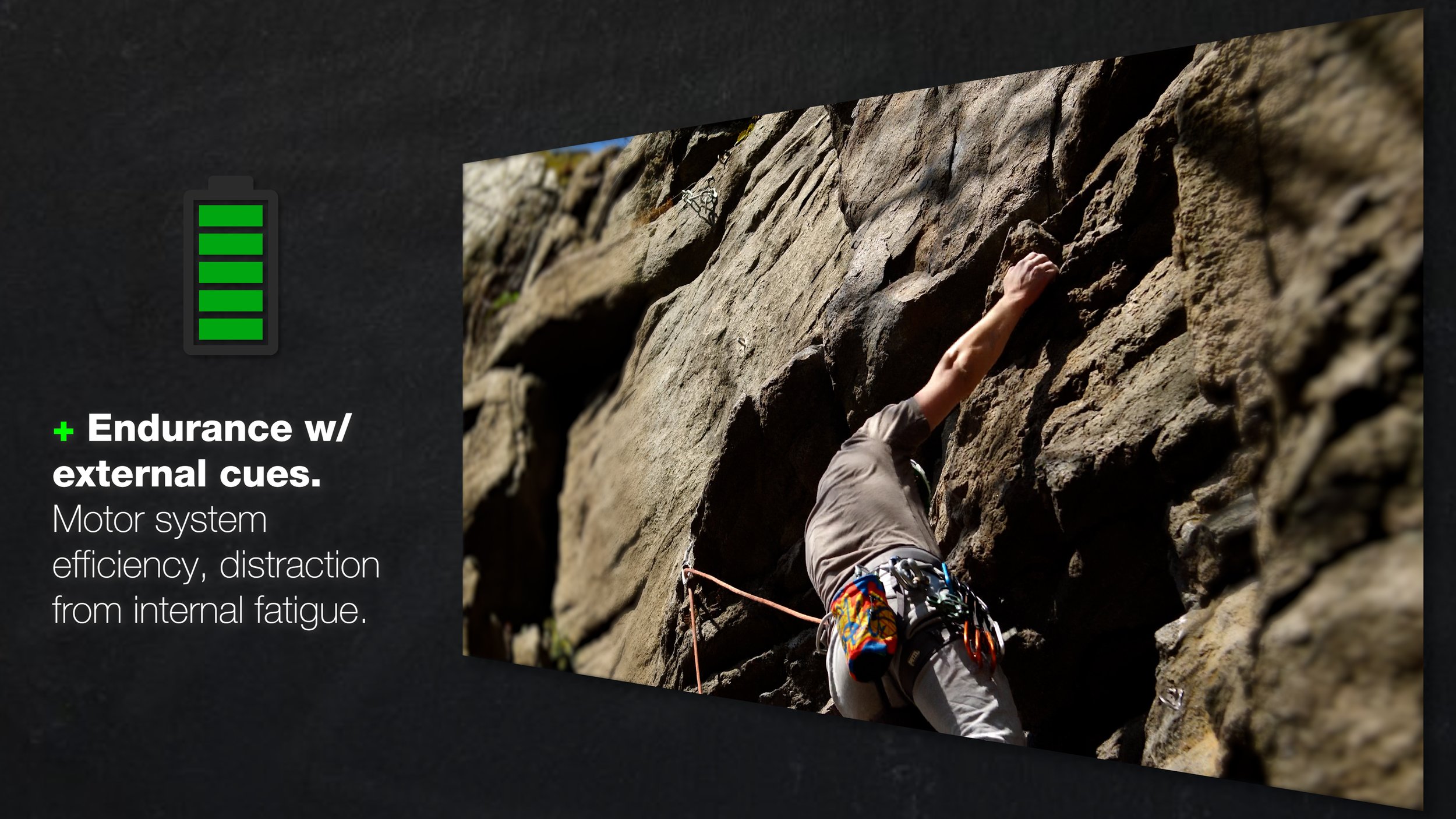

External cues create an outward intention. They promote greater movement efficiency by allowing our body to “take the reins” and do whatever it needs to do to accomplish the goal, reducing “noise in the system” or slow-downs due to internal focus. Whether it’s maximizing strength gains by performing the movement as efficiently as possible, improving coordination by aiming for a simple target, or increasing endurance by distracting us from fatigue, external cues are generally best when we want to optimize performance and fluidity.

Essentially, we should use internal cues to help us exert granular control over a specific part of our body, which will cost some overall performance in our motor control system. We should use external cues to help us with the inverse.

We should, of course, allow for some variability here, but that guideline will hold true in most circumstances.[11]

Where’s the Proof?

So where’s the proof of all this? Turns out there are tons of neat examples in the research and we can’t possibly cover all the cool mechanisms at play, so let’s cover a few of the highlights and we’ll link the in-depth material in the show notes.

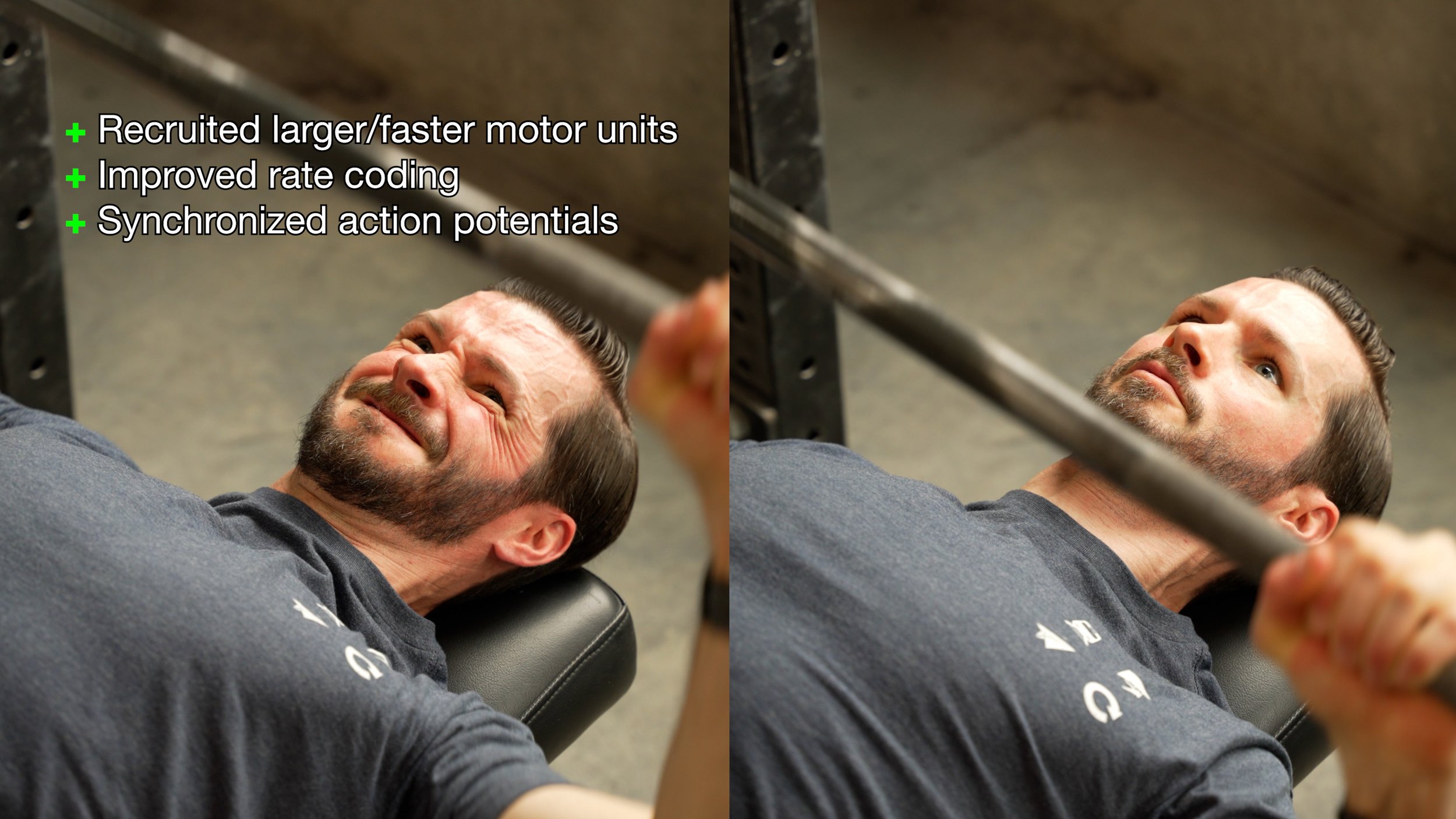

When it comes to strength, my favorite study is that one from 2012 about completing reps quickly. They studied 20 trained participants doing bench press, and the ones intent on completing the rep near max speed ended up with significantly higher increases in strength and speed than the control group, despite both groups using the same relative weight (85% of their 1RM). One reason for this is likely that simply having the intention to lift faster recruited larger and faster motor units/muscle fibers. Additionally, it probably increased the speed and efficiency of brain signals sent to the muscle, optimizing rate coding. Finally, it may have improved synchronization of action potentials as well.[14]

These reasons are part of why we recommend experienced climbers or athletes consider performing their strength exercises with the intent to move as fast as possible as long as they maintain form. In many circumstances, this will lead to movement that actually is faster, which is great. But in some cases, like with heavy weights, the speed may not change much, though the benefits of the intention will still be present.

Cueing can cause more immediate strength improvements as well. In fact, this random Swedish YouTuber [footage of Emil] recently provided a great example when he noticed that cueing himself to literally squeeze holds harder led to better strength on pinches. As it turns out, multiple research articles support external cues for increasing acute strength… including grip strength! Perhaps this random guy would be better at climbing if he imagined crushing every hold!

When it comes to other aspects of performance besides strength, we see all kinds of interesting effects from intention research:

Increased coordination with complex movements using external cues, likely due to the better motor system performance we discussed earlier, resulting in more reflexive movement and optimized motor learning. [11]

Increased sprint speed with external cues, probably for similar reasons. [9]

Improved muscular endurance using external cues, probably for similar reasons but also because focusing too much on internal sensations like muscle burn, fatigue, and lack of oxygen can make them feel exaggerated and distract from optimal performance. [4][6]

Increased hypertrophy with internal cues, likely due to reduced movement compensations and more attention paid to fatiguing the target muscle.[1]

And improved skill acquisition, as previously explained with the three stages of motor learning. [2][13][15][16]

While external cues clearly steal the show for the majority of performance benefits, we should be aware that both types of cues can actually be used together for further benefits.

Advanced Cueing Techniques?

So, before we wrap things up, let’s see how external and internal cues can be used in sequence and in tandem for more advanced functions.

Cues used in sequence can further aid complex learning. For example, we could use an internal cue to help us hone in on specific muscle activation. Once learned, it could then help us master an external cue on the wall that benefits from the improved awareness. It can work the other way around, too. If we’re having trouble engaging a particular muscle, we can use an external cue that causes us to use it, allowing us to learn the feeling and eventually activate that muscle on command with an internal cue

Finally, cues can also be used in tandem. For example, when we visualize our project off the wall, we may rehearse specific muscle activation (internal) as well as the positioning of our limbs in space (external). In the most advanced stages, when our skill foundation has become highly optimized and reflexive, we’re able to narrow our focus down to only the most salient internal and external intentions, entering the flow state with ease and maximizing our performance.

What Have We Learned?

Okay, let’s sum up what we’ve learned.

Many climbers suffer plateaus due to lack of intentional learning or effort.

In general, paying more attention to your intention while climbing and training has a vast array of benefits, and cues are a simple way to put that into practice.

Internal cues should generally be used when specific muscle activation is needed.

External cues should generally be used when optimized performance and movement learning is needed.

Cues can be used together for further improvements in motor learning, skill acquisition, and “flow state” sends.

If you take one thing away from this video, it should be to come up with a useful new cue to practice during your next climbing session. Filming yourself will go a long way to helping you identify issues and possible fixes.

Conclusion

Thanks so much to everyone who supports free, science-based content on this channel by subscribing, buying t-shirts, purchasing gear through our affiliate links, and just generally sharing the psych. Until next time: train, climb, send, and repeat… with intention!

RESEARCH

Schoenfeld BJ, Vigotsky A, Contreras B, et al. Differential effects of attentional focus strategies during long-term resistance training. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;18(5):705-712. doi:10.1080/17461391.2018.1447020 [1]

Aiken CA, Becker KA. Utilizing an internal focus of attention during preparation and an external focus during execution may facilitate motor learning. Eur J Sport Sci. 2023;23(2):259-266. doi:10.1080/17461391.2022.2042604 [2]

Marchant DC. Attentional focusing instructions and force production. Front Psychol. 2011;1:210. Published 2011 Jan 26. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00210 [3]

Schücker L, Hagemann N, Strauss B, Völker K. The effect of attentional focus on running economy. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(12):1241-1248. doi:10.1080/02640410903150467 [4]

Schücker L, Knopf C, Strauss B, Hagemann N. An internal focus of attention is not always as bad as its reputation: how specific aspects of internally focused attention do not hinder running efficiency. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2014;36(3):233-243. doi:10.1123/jsep.2013-0200 [5]

Grgic J, Mikulic P. Effects of Attentional Focus on Muscular Endurance: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19(1):89. Published 2021 Dec 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010089 [6]

Wiseman S, Alizadeh S, Halperin I, et al. Neuromuscular Mechanisms Underlying Changes in Force Production during an Attentional Focus Task. Brain Sci. 2020;10(1):33. Published 2020 Jan 7. doi:10.3390/brainsci10010033 [7]

Grgic J, Mikulic I, Mikulic P. Acute and Long-Term Effects of Attentional Focus Strategies on Muscular Strength: A Meta-Analysis. Sports (Basel). 2021;9(11):153. Published 2021 Nov 12. doi:10.3390/sports9110153 [8]

Li D, Zhang L, Yue X, Memmert D, Zhang Y. Effect of Attentional Focus on Sprint Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):6254. Published 2022 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph19106254 [9]

Massimo Filippi, Sarasso Elisabetta, Noemi Piramide, Federica Agosta, Chapter Fourteen - Functional MRI in Idiopathic Parkinson's Disease, Editor(s): Marios Politis, International Review of Neurobiology, Academic Press, Volume 141, 2018, Pages 439-467, ISSN 0074-7742, ISBN 9780128154182, ttps://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2018.08.005. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0074774218300722) [11]

Yamada M, Lohse KR, Rhea CK, Schmitz RJ, Raisbeck LD. Practice-Not Task Difficulty-Mediated the Focus of Attention Effect on a Speed-Accuracy Tradeoff Task. Percept Mot Skills. 2022;129(5):1504-1524. doi:10.1177/00315125221109214 [11]

McNicholas K, Comyns TM. Attentional Focus and the Effect on Change-of-Direction and Acceleration Performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(7):1860-1866. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003610 [12]

Hitchcock DR, Sherwood DE. Effects of Changing the Focus of Attention on Accuracy, Acceleration, and Electromyography in Dart Throwing. Int J Exerc Sci. 2018;11(1):1120-1135. Published 2018 Oct 1. [13]

Padulo J, Mignogna P, Mignardi S, Tonni F, D'Ottavio S. Effect of different pushing speeds on bench press. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(5):376-380. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1299702 [14]

Bredin SS, Dickson DB, Warburton DE. Effects of varying attentional focus on health-related physical fitness performance. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38(2):161-168. doi:10.1139/apnm-2012-0182 [15]

Halperin I, Hughes S, Panchuk D, Abbiss C, Chapman DW. The Effects of Either a Mirror, Internal or External Focus Instructions on Single and Multi-Joint Tasks. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166799. Published 2016 Nov 29. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166799 [16]

DISCLAIMER

As always, exercises are to be performed assuming your own risk and should not be done if you feel you are at risk for injury. See a medical professional if you have concerns before starting new exercises.

Written and Presented by Jason Hooper, PT, DPT, OCS, SCS, CAFS

IG: @hoopersbetaofficial

Filming and Editing by Emile Modesitt

www.emilemodesitt.com

IG: @emile166